An entrepreneurial state

China is bidding to be the innovation superpower of the 21st century. Will it succeed?

As the Fourth Industrial Revolution gathers pace and the timeline to net zero contracts, global progress is set to depend ever more heavily on technological innovation. Those countries that can build and maintain leadership in critical technologies like artificial intelligence (AI), quantum computing, and clean energy are likely to reap massive rewards, both politically and economically – a fact China has long recognized and encoded in its industrial policy. In this context, it is worth asking the extent to which China’s state-centric model will aid or undermine its efforts to achieve technology dominance across multiple strategic sectors.

The state as innovation catalyst

The state as innovation catalyst

Perhaps the most omnipresent piece of innovation in our lives today is the smartphone, a gadget that captures our attention so fully that most of us are never willingly parted from it. Indeed, many view the smartphone as an archetypal triumph of private sector innovation: physical proof of capitalism’s power to incentivize and manifest life-changing products and services.

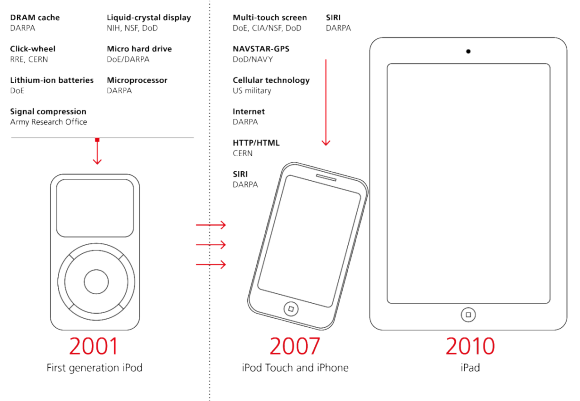

However, as Mariana Mazzucato reminds us in her book ‘The Entrepreneurial State’,1 “While the products owe their beautiful design and slick integration to the genius of Jobs and his large team, nearly every state-of-the-art technology found in the iPod, iPhone and iPad is an often overlooked and ignored achievement of the research efforts and funding support of the government and military.” From touchscreen technology to GPS, and from SIRI to the internet, Apple’s 2007 launch of its first iPhone was built on a whole suite of enabling technologies whose origins lie in state-funded development.

Exhibit 1: What makes the iPhone so ‘Smart?'

Exhibit 1: What makes the iPhone so ‘Smart?'

Acknowledging these technological roots doesn’t make the iPhone any less spectacularly useful, and of course the combination of these particular technologies in this particular format remains a special feat of commercial creativity, whose benefits Apple continues to reap to this day. Innovation in all fields is iterative; today’s breakthroughs rely on those of prior generations.

But the iPhone technology dissection does inject important nuance into the debate about innovation, and what conditions best produce it. Doctrinaire economic liberals often fetishize innovation as a uniquely capitalist phenomenon, an economic miracle brought about by free competition that succeeds despite the supposed ‘dead hand’ of the state.

According to Mazzucato, this is at best an oversimplification, at worst a contradiction of reality. In her thesis, the state instead plays a key role in the innovation chain. Through its willingness to underwrite the risky, the theoretical, and the expensive, the state has often laid the foundations on which private enterprise has realized the world’s greatest commercial breakthroughs.

Recent history provides plenty of support for such arguments. As Mike Nell, senior equity analyst and portfolio manager at UBS Asset Management, points out, “the US space programme of the 50s and 60s yielded a glut of technologies that were later to be commercialized to spectacular success, including satellites, microchips, water filtration systems, and infant formula.” And in Asia, South Korea’s entry into the semiconductor memory industry is often cited as a textbook example of the so-called ‘developmental state’, and has of course achieved overwhelming success.

The US space programme of the 50s and 60s yielded a glut of technologies that were later to be commercialised to spectacular success, including satellites, microchips, water filtration systems, and infant formula.

Seen in this light, the optimal conditions for innovation are likely to emerge from an interplay between the public and private spheres, with the state fostering foundational infrastructure and breakthrough technology, and the private sector building and iterating on these with a consumer demand focus. Such thinking has breathed fresh life into once-fashionable industrial policy ideas now being exhumed in the US and Europe, where governments are once again directly supporting key industries in pursuit of strategic self-sufficiency.

Chinese exceptionalism

If Mazzucato’s thesis is broadly correct, what are its implications for investor analyses of China, a massive, activist state with a declared intention to achieve dominance across a range of strategically critical technologies?

Before getting too carried away, Nell injects some important nuance to how we should think about China’s approach. “The US government was never trying to invent the “consumer technologies of tomorrow” when it invested efforts in developing critical smartphone technologies. It was trying to solve important, strategic problems that would ensure dominance of the battlefield of tomorrow.”

The US government was never trying to invent the “consumer technologies of tomorrow” when it invested efforts in developing critical smartphone technologies.

He argues that, by contrast, the Chinese appear to be skipping this step and trying to fund winners in technologies likely to be focused on consumer markets. “This is more like Japan’s MITI industrial policy strategy of the 70’s and 80’s than the US’s DARPA and space program efforts of the past,” he says.

Regardless, China’s ambitions to be an innovation superpower have been well publicized by its leadership. And it has achieved remarkable success to this end, especially in what Dr. Keyu Jin calls ‘One-to-N’ innovations, which are iterative improvements on so-called ‘Zero-to-One’ innovations – true fundamental breakthroughs. So while China was once dismissed as a mere copier of Western technology, it is now producing world-leading technologies of its own, and Chinese companies are being copied by their competitors in fields from social media to online payment. According to the World Economic Forum, China has birthed more than 300 unicorns, and has attracted only marginally less start-up funding than the US.

Hyper-adaptive and hyper-adoptive

How has China achieved all this? The so-called ‘entrepreneurial state’ has clearly played its part. China’s willingness to act as its own venture capital firm, to protect nascent industries from competition, and to invest heavily in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) education as well as research and development (R&D), are all well known. But these are not the only factors at work; as Dr. Keyu Jin points out, China benefits from a range of other important characteristics.

Ferocious competition, for instance, is every bit as prevalent in the Chinese market as anywhere else. Being relatively undeveloped in comparison to the US and Europe has allowed China to benefit from technology leapfrogging, developing whole new tech ecosystems in, say, digital payments, without the encumbrance of legacy systems.

The simple scale of China’s domestic market is another overlooked factor: if data is indeed the new oil, Chinese firms, which can interact with up to 1.4bn consumers, are richer in it than those in any other country. Having access to this kind of market gives Chinese innovators an unparalleled number of transactions and interactions to learn from, a process that arguably amounts to an built-in innovation advantage.

As the Harvard Business Review has argued, it is not merely the size of the Chinese market but its unique characteristics that create this advantage. Chinese consumers, having lived through an extraordinary degree of change, are uniquely comfortable with, and receptive to, rapid social and technological evolution, making them incredibly willing adopters of innovative tech.2

As Zak Dychtwald argues in the piece: “It’s that aspect of China’s innovation ecosystem – its hundreds of millions of hyper-adoptive and hyper-adaptive consumers – that makes China so globally competitive today. In the end, innovations must be judged by people’s willingness to use them. And on that front China has no peer.”3Indeed, while by 2019 Apple Pay had been used by less than a quarter of Americans, WeChat pay had become almost ubiquitous among China’s smartphone users.4

It’s that aspect of China’s innovation ecosystem – its hundreds of millions of hyper-adoptive and hyper-adaptive consumers – that makes China so globally competitive today.

Technology monopoly

An especially detailed look at China’s innovation profile comes from research published by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI). And while only one of many sources, their Critical Technology Tracker has highlighted a large number of strategically important technologies in which China already dominates, as well as many more in which it is well-positioned to achieve, as ASPI puts it, ‘technology monopoly’.

Table 1: Lead country and technology monopoly risk

Technology | Technology | Lead country | Lead country | Technology monopoly risk | Technology monopoly risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Technology | Advanced materials and manufacturing | Lead country | - | Technology monopoly risk | - |

Technology | 1. Nanoscale materials and manufacturing | Lead country | China | Technology monopoly risk | High |

Technology | 2. Coatings | Lead country | China | Technology monopoly risk | High |

Technology | 3. Smart materials | Lead country | China | Technology monopoly risk | Medium |

Technology | 4. Advanced composite materials | Lead country | China | Technology monopoly risk | Medium |

Technology | 5. Novel metamaterials | Lead country | China | Technology monopoly risk | Medium |

Technology | 6. High-specification machining processes | Lead country | China | Technology monopoly risk | Medium |

Technology | 7. Advanced explosives and energetic materials | Lead country | China | Technology monopoly risk | Medium |

Technology | 8. Critical minerals extraction and processing | Lead country | China | Technology monopoly risk | Low |

Technology | 9. Advanced magnets and superconductors | Lead country | China | Technology monopoly risk | Low |

Technology | 10. Advanced protection | Lead country | China | Technology monopoly risk | Low |

Technology | 11. Continuous flow chemical synthesis | Lead country | China | Technology monopoly risk | Low |

Technology | 12. Additive manufacturing (incl. 3D printing) | Lead country | China | Technology monopoly risk | Low |

Technology | Artificial intelligence, computing and communications | Lead country | - | Technology monopoly risk | - |

Technology | 13. Advanced radiofrequency communications (incl. 5G and 6G) | Lead country | China | Technology monopoly risk | High |

Technology | 14. Advanced optical communications | Lead country | China | Technology monopoly risk | Medium |

Technology | 15. Artificial intelligence (Al) algorithms and hardware accelerators | Lead country | China | Technology monopoly risk | Medium |

Technology | 16. Distributed ledgers | Lead country | China | Technology monopoly risk | Medium |

Technology | 17. Advanced data analytics | Lead country | China | Technology monopoly risk | Medium |

Technology | 18. Machine learning (incl. neural networks and deep learning) | Lead country | China | Technology monopoly risk | Low |

Technology | 19. Protective cybersecurity technologies | Lead country | China | Technology monopoly risk | Low |

Technology | 20. High performance computing | Lead country | USA | Technology monopoly risk | Low |

Technology | 21. Advanced integrated circuit design and fabrication | Lead country | USA | Technology monopoly risk | Low |

Technology | 22. Natural language processing (incl. speech and text recognition and analysis) | Lead country | USA | Technology monopoly risk | Low |

Technology | Energy and environment | Lead country | - | Technology monopoly risk | - |

Technology | 23. Hydrogen and ammonia for power | Lead country | China | Technology monopoly risk | High |

Technology | 24. Supercapacitors | Lead country | China | Technology monopoly risk | High |

Technology | 25. Electric batteries | Lead country | China | Technology monopoly risk | High |

Technology | 26. Photovoltaics | Lead country | China | Technology monopoly risk | Medium |

Technology | 27. Nuclear waste management and recycling | Lead country | China | Technology monopoly risk | Medium |

Technology | 28. Directed energy technologies | Lead country | China | Technology monopoly risk | Medium |

Technology | 29. Biofuels | Lead country | China | Technology monopoly risk | Low |

Technology | 30. Nuclear energy | Lead country | China | Technology monopoly risk | Low |

Technology | Quantum | Lead country | - | Technology monopoly risk | - |

Technology | 31. Quantum computing | Lead country | USA | Technology monopoly risk | Medium |

Technology | 32. Post-quantum cryptography | Lead country | China | Technology monopoly risk | Low |

Technology | 33. Quantum communications (incl. quantum key distribution) | Lead country | China | Technology monopoly risk | Low |

Technology | 34. Quantum sensors | Lead country | China | Technology monopoly risk | Low |

Technology | Biotechnology, gene technology and vaccines | Lead country | - | Technology monopoly risk | - |

Technology | 35. Synthetic biology | Lead country | China | Technology monopoly risk | High |

Technology | 36. Biological manufacturing | Lead country | China | Technology monopoly risk | Medium |

Technology | 37. Vaccines and medical countermeasures | Lead country | USA | Technology monopoly risk | Medium |

Technology | Sensing, timing and navigation | Lead country | - | Technology monopoly risk | - |

Technology | 38. Photonic sensors | Lead country | China | Technology monopoly risk | High |

Technology | Defense, space, robotics and transportation | Lead country | - | Technology monopoly risk | - |

Technology | 39. Advanced aircra engines (incl. hypersonics) | Lead country | China | Technology monopoly risk | Medium |

Technology | 40. Drones, swarming and collaborative robots | Lead country | China | Technology monopoly risk | Medium |

Technology | 41. Small satellites | Lead country | USA | Technology monopoly risk | Low |

Technology | 42. Autonomous systems operation technology | Lead country | China | Technology monopoly risk | Low |

Technology | 43. Advanced robotics | Lead country | China | Technology monopoly risk | Low |

Technology | 44. Space launch systems | Lead country | China | Technology monopoly risk | Low |

ASPI used its March release of the tracker to warn that: “China has built the foundations to position itself as the world’s leading science and technology superpower, by establishing a sometimes stunning lead in high-impact research across the majority of critical and emerging technology domains”, and that this lead “coupled with successful strategies for translating research breakthroughs to commercial systems and products that are fed into an efficient manufacturing base – could allow China to gain a stranglehold on the global supply of certain critical technologies.”

According to ASPI, China has achieved this position by concentrating technological expertise, a deliberate strategic goal underpinned by its strong educational base, preponderance of STEM researchers and institutions, significant investment in science and tech R&D, and direct support for strategic industries.

As with any such effort to quantify the complex and dynamic, ASPI’s tracker is open to methodological challenge, but the broad thrust of its conclusions surely warrants consideration, and there is certainly growing Western recognition of China’s technological progress. Indeed, such observations are already fuelling a response, with both governments and multinationals scrambling to repatriate manufacturing capability and protect supply chains. The net result for the global economy is likely to be diminished manufacturing efficiency as capital equipment and production capacity is restored to Europe and the US, rather than concentrated in proven centers of excellence such as Taiwan.

Productivity and profit

Nell agrees that China’s technological ambitions have sometimes been dismissed prematurely, and that its significant investments are likely to buy it dominance in several key technologies, including solar panels, electric vehicles (EVs), and semiconductors.

In semiconductors, for instance, he warns that while today’s Chinese offerings are often seen as underdeveloped, they are likely to make rapid progress building off the applications they are servicing today, which in the long term may prove to be a route to market dominance. He cites Huawei’s recent unveiling of its Mate 60 Pro, powered by SMIC’s 7-nanometer processor, as a wake-up call for the industry, suggesting China’s chipmaking has evolved much further than was generally believed.

But, as Nell points out, there is an important distinction to make between market dominance and profitability. Investors need to ask not only whether China is likely to dominate a technology, but whether it can do so profitably: “They subsidize a lot of industries that are essentially unprofitable, so it's very difficult in some of them for US and Europe to keep up. But you have to ask yourself, is it worth keeping up if it's an unprofitable enterprise? In many cases, it is not. Electric vehicles would be a good example, where it looks like they're going to be, perhaps the winner. But the question is, how profitable will they be in electric vehicles?”

When it comes to China assessments, therefore, the concerns of investors are not necessarily the same as those of politicians, so it’s important to be clear about where one’s priorities lie. As Nell explains: “what matters from a stock perspective, in our view, is the intrinsic value of the stock, which is the sum of the discounted cash flows that the company will generate over its life. We have to hold the Chinese stocks to the same standard that we hold all stocks, and those where we can't see line-of-sight profitability are probably going to be uninvestable.” He urges investors not to get too caught up in the hype of things and conclude China is somehow winning by investing in unprofitable areas and dominating them.

Jia Tan, Head of Research for O’Connor China Equity Long/Short, believes there are clear investment opportunities. “Those [companies] that develop and integrate AI applications into areas such as ecommerce, online advertising/gaming and molecular development biology could also benefit greatly. In addition, we believe that long-only opportunities can also be found in the semiconductor sector,” he says.

Renewable dominance

It is important to note that China´s dominance of EV´s and solar PV benefits Chinese society and the Chinese leadership even if it never results in good returns for investors. As Ellis Eckland, Portfolio Manager - Global Equities, points out, “dominating EV´s and solar PV has great strategic benefit as it essentially forces the West to choose between 1) a rapid energy transition (impossible without China´s participation) or 2) any kind of hard rivalry with China (war, economic decoupling, strong sanctions or trade barriers).”

The scale and resulting low cost that comes from dominating solar PV and eventually wind will also have strong indirect benefits for Chinese industry . This is because it will likely result in a lower cost of renewable electricity for production resulting in a strategic cost advantage for low carbon green industrial goods. This advantage in downstream goods that will be exported to markets that care about embedded emissions (i.e., Europe, potentially followed by the rest of the OECD) could benefit Chinese industrial profitability more than it is hurt by over allocation of capital to wind and solar production. “More importantly (at least to the Chinese leadership), dominance higher value downstream green manufacturing will shift relatively high wage jobs to China which may help solve their youth unemployment problems and enable them to move to a higher level of industrial development,” says Eckland.

Furthermore, while both EVs and solar PV are quite commoditized and thus will never develop the market positions of Netflix or Amazon, China´s dominance could result in an economy of scale at the ecosystem level. This would offer broad scale benefits to the entire Chinese solar "cluster" and EV "cluster" resulting in most Chinese companies in these sectors generating superior profitability versus global competitors.

Nevertheless, as Sino-American trust deteriorates, many in the West wonder how China might use that domination, if established. A Chinese stranglehold on any strategic technology would be widely seen as a threat, offering China a powerful lever with which to coerce governments and businesses and artificially inflate prices through supply restriction – if it chose to do so. Such fears have seen both the US and EU implement ‘CHIPS’ acts to promote supply chain resilience in semiconductors, and have only been magnified by China’s recent export curbs on gallium and germanium, important minor metals for semiconductor manufacturing.7

Moves of this kind remind the West that many of its most innovative companies are still heavily dependent on Chinese-owned or processed materials for production of next-generation technologies.

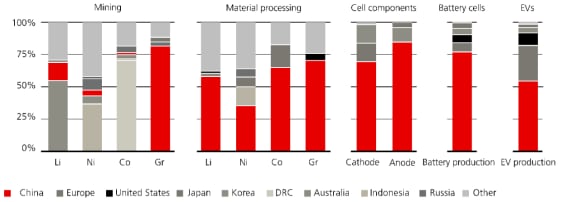

China´s dominance in the energy transition is a good example. In 2023 China invested USD543 billion in the energy transition, nearly three times as much as the European Union (USD180 billion) and nearly four times as much as the United States (USD141 billion). This investment has resulted in a completely dominant position in key technologies like EV batteries.8

As Eckland points out, “China produces 79% of the world´s EV battery cells, 70% of battery anodes, 85% of battery cathodes and 66% of separators and rare earth elements (REE), which are critical to EV motors where China produces and processes over 60% of the world supply.” 9

China produces 79% of the world´s EV battery cells, 70% of battery anodes, 85% of battery cathodes and 66% of separators and rare earth elements (REE), which are critical to EV motors where China produces and processes over 60% of the world supply.

And their dominant position extends upstream to the key metals used to make batteries and EVs. Here China refines 68% of the world’s nickel, 40% of the world´s copper, 59% of lithium and 73% of the world´s cobalt. Eckland argues this “will make it difficult for other countries to source enough of these metals to reduce China´s share of battery production.”10

China is also the low-cost leader in modern renewables manufacturing. It is responsible for 80% of the world´s solar manufacturing capacity11, and non-Chinese manufacturers almost invariably need government subsidies or trade barriers to stay in business. China is also the lowest-cost producer of wind turbines by some margin and, as Eckland says, “they now appear to be making huge strides in lowering the cost of manufacturing hydrogen electrolyzers as well.”

Chart 1: China dominates the entire downstream EV battery supply chain

Geographical distribution of the global EV battery supply chain

Engineering innovation

China’s success in fostering innovation is increasingly difficult to ignore. This success is attributable to many factors, including its extraordinary market characteristics, its competition, and the activist role of the state as both a promoter and protector of key nascent technologies. If the best conditions for innovation really do emerge from an interplay between the public and private spheres, then China clearly has reason to be optimistic about its technology leadership ambitions.

Of course, there is a counter narrative. The 2022 Global Innovation Index, published by The World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), places China outside the world’s top ten countries. The US remains an innovation powerhouse, spending over USD 700 billion per year on R&D, and hosting four of the world’s top R&D spenders (Amazon, Alphabet, Microsoft, Apple).

Silicon Valley remains a unique concentration of talent, capital, and aspiration, and the US is still responsible for a huge proportion of the world’s fundamental technology breakthroughs. As Dr Jin warns: “while China is achieving remarkable mastery of One-to-N technologies particularly when it comes to internet applications and business model design, it is not yet poised to consistently make Zero-to-One trailblazing innovations. For this to happen, there will need to be profound changes to China's civil society, its markets and the role of the state.” In the meantime, of course, Western countries are responding more proactively to China’s growing technology prowess.

While China is achieving remarkable mastery of One-to-N technologies particularly when it comes to internet applications and business model design, it is not yet poised to consistently make Zero-to-One trailblazing innovations.

The reality is that both Chinese and Western systems will continue to spawn innovation and build profitable enterprises on top of it. At the geopolitical level, policymakers and companies will increasingly seek to mitigate the risk of Chinese technology monopoly in the coming years, implying a net reduction in technology transfer and innovation at the global level, with unfortunate implications for net-zero goals. But as the political rhetoric heats up, investors should be wary of letting it blind them to the opportunities China offers.

About the authors

Ellis Eckland

Portfolio Manager Climate Action

Ellis Eckland, lead portfolio manager for UBS Climate Action and UBS Future Energy Leaders strategies. Also a Senior Investment Analyst on UBS AM's Global Equity team, focusing on renewable energy, materials, and conventional energy sectors. Ellis joined UBS AM in 2010. Former Chairman and CIO of Eckland Capital Management. Previous roles at Frontpoint Partners and Putnam Investments as energy and materials analyst. Former US Naval Intelligence Officer awarded Joint Service Commendation Medal.

Michael Nell

Senior analyst in Technology, Communication Services and Media sectors

Mike Nell is the senior analyst in Technology, Communication Services and Media sectors within the Global Intrinsic Value team. He is also Lead portfolio manager for the Technology Opportunity Fund and the US Opportunity Unconstrained Strategy. His responsibilities include fundamental company and industry-level research. His industries of focus include the cable, computer hardware, electronic manufacturing services, internet, IT Services, printing and imaging, semiconductor, semiconductor capital equipment, software and telecom industries.

Jia (TJ) Tan

Head of Research, China Long/Short, based in Shanghai

TJ joined O'Connor in 2019 and has over 12 years of investment industry experience, particularly investing in the China markets.

Get in touch

Whether you have a question or a request, we will be happy to get in touch with you.