Article

There’s a problem with GDP

GDP is an incomplete measure. It counts the price of everything but the impact of nothing

![]()

header.search.error

Article

GDP is an incomplete measure. It counts the price of everything but the impact of nothing

Does money buy happiness? Most of us would probably agree that it doesn’t hurt.

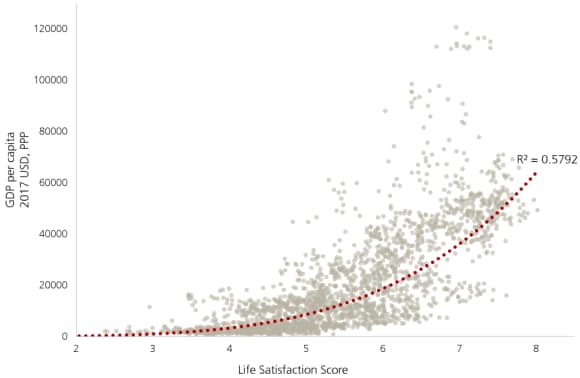

There are certainly signs that a link exists between GDP, or the value of an economy’s output of goods and services, and happiness levels. Plotting the data for 149 countries between 2003 and 2021 reveals a significant relationship between GDP per capita and life satisfaction.

GDP per Capita vs Life Satisfaction Score

Constant 2017 $, Purchasing Power Parity, 2003-21

Yet as compelling as this relationship may appear, we do not believe it tells the whole story. Most notably, GDP increases have diminishing returns when it comes to happiness. A 2013 study1 found that countries’ life satisfaction levels tend to peak at the point that GDP per capita reaches around $30,000 (PPP, 2005 $). In a similar vein, a canonical 1974 study2 by Richard Easterlin (who published an update3 in 2020) famously found that while the US’s real GDP per capita rose almost two thirds between 1946 and 1970, the average person’s happiness barely increased over the same period.

To put it another way, it appears that the wealthier a country becomes, the less likely people’s wants and needs will continue to be satisfied simply by consuming more things. Added to that, increased GDP levels often come with social and environmental costs. For instance, increasing economic growth rates in some economies4 have been accompanied by mounting levels of toxic air pollution. The higher GDP rate means the average person has more money to spend on things they want, but they must also live in increasingly particulate-filled streets that make their daily lives less pleasant and may potentially cause health issues. In other words, life satisfaction cannot be encapsulated by GDP alone.

The shortcomings of the GDP metric

The prominence of GDP has arguably dominated economics and politics across most of the world for 80 years. We believe this output approach has become increasingly outmoded. By failing to take into account environmental and social impacts, output-focused economics is increasingly failing in its primary purpose—to provide a sound basis for policy and capital allocation decisions.

In our most recent white paper “The Rise of the Impact Economy,”5 we argue that output economics needs to make way for impact economics. What would this mean in practice? Where output economics focuses on production alone (loosely speaking), impact economics would widen its scope to also include the well-being of people and the planet.

Introducing this change in approach will not be easy. One of the attractions of GDP as a metric is that it appears to neatly encapsulate the price of everything (goods) and everybody (services). However, this apparent simplicity is also GDP’s principle failing. It doesn’t, for instance, consider the cost of a company negligently including child labor in its supply chain, or the environmental and biodiversity costs of clearing acres of rainforest to make way for cattle grazing land.

A measurable improvement

The challenge is not necessarily to entirely replace GDP but to design a more holistic and therefore more accurate measure that incorporates the impact of output in addition to its monetary value. Under this model, output actions today that offer immediate growth but have longer term costs (say, a new oil field) would not be given the same weight in the national accounts as growth actions that are sustainable (such as the production of energy conserving insulation).

It will be a challenge to convince GDP-focused nations, societies, and industries to adopt this broader approach to economic analysis. Introducing the impact economy will depend on finding ways to measure things which are often hard to quantify and have costs or benefits that may take a long time to materialize. This is not to say that impact data does not exist—it does, but not yet in aggregate in a reliable, consistent, or transparent form. It needs to become better and more standardized. And the need is pressing.

It has become increasingly clear that making ever more things does not necessarily raise levels of wellbeing. Indeed, if nations continue to do so they will only intensify the climate crisis, to the detriment of national levels of happiness in the years and decades to come. Economists, financial institutions, data providers and regulators all have vital roles to play in creating, standardizing, and popularizing the tools needed to better understand the impact of output. The time to do so is now.

The author is grateful for feedback from: Dean Turner, William Nicolle, Jackie Bauer, Mike Ryan, Richard Morrow.

For further information, please read our thought leadership disclaimer