Article

Unpacking the true cost of plastic

Plastic may seem cheap, but its real cost is much greater than we realize. Reducing it will require shifting from a linear to a more circular plastics economy.

![]()

header.search.error

Article

Plastic may seem cheap, but its real cost is much greater than we realize. Reducing it will require shifting from a linear to a more circular plastics economy.

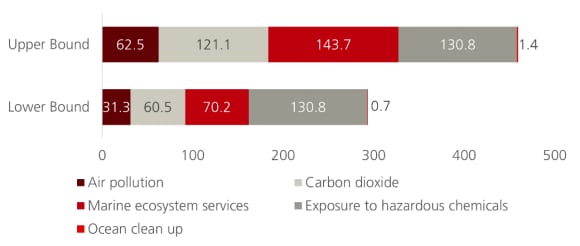

Plastic pollution is expensive. Currently, the social and environmental costs are estimated at USD 300–460bn per year (Figure 1). This includes the health costs stemming from associated emissions, air pollution, and exposure to hazardous chemicals, as well as the cost of ocean clean up and lost marine ecosystem services.1 With microplastics now being found in human blood and the health consequences of that yet unknown, the true cost could be significantly larger.2

Figure 1: Paying the bill

The estimated annual cost of externalities in a business-as-usual scenario

Dead ends to roundabouts

The full cost of plastic does not only stem from its externalities. The disposal system is expensive, too. A major part of the problem is that the plastics supply chain is mostly linear, with materials produced new and used only once. An estimated 90–95% of plastic production is “virgin” plastic3 and over two-thirds of the 430 million tons of plastic produced globally each year is for short-lived, single-use products, like packaging or bags. Moreover, product disposal is mismanaged—barely 10% of plastic gets recycled each year. In 2019, 82 million tons of plastic waste was collected and then released or deposited, such that the waste could get into the natural environment, e.g., in dumpsites or landfills.4 As a result, over 100 million tons of plastics have accumulated in rivers and lakes, and 30 million tons in the ocean. The total cost to governments of managing plastic waste between 2021 and 2040 could reach up to USD 670bn, with the cost of inaction for businesses potentially reaching USD 100bn over the same timeframe.5

Achieving a circular plastics economy

In 2023, the UN Environmental Program published a report outlining a systems change scenario to end plastic pollution and create a circular economy. The plan envisages curbing unnecessary plastic use and reducing plastic pollution by expanding the recycling market. Under this scenario, savings of USD 1.3tr could be realized, considering investment, operational, and management costs, and recycling revenues. A further estimated USD 3.3tr could be saved from avoided externalities, like health costs. The report highlights the huge societal value of a sustainable plastics economy. Each dollar saved in direct costs could save twice that amount in indirect costs.6

Turning this plan into reality will require a change in economic incentives. On the supply side, scaling back fossil fuel subsidies is needed to raise the production costs of virgin plastics and promote investment in recycled plastics, non-plastic substitutes, and business models. To help redirect plastics use toward only the most essential cases, a freeze in production and caps or reduction targets are also likely to be necessary. 17% of short-lived plastic products could be replaced with sustainable substitutes, while switching to sustainably sourced paper from flexible plastic could reduce about 25% greenhouse gas emissions.7

Alternatives to plastics are not without their own drawbacks—production costs of sustainable alternative materials are about 1.5 to 2 times higher than plastic on average and need to be carefully handled to avoid increasing greenhouse gas emissions and contaminating waste streams. Case-by-case product life cycle assessments are required to ensure the substitutes meet sustainability and national health standards.8

On the demand side, an analysis by the OECD suggests that increasing taxes on plastic packaging at a global scale would roughly double its cost and help moderate consumption, increase demand for secondary plastics, and boost investment in collection and recycling systems.

Product design is also important. Policies that incentivize designs that facilitate circularity rather than single use are essential. These are most effective when directly targeting product characteristics such as weight or recyclability. According to the UN, it is economically feasible to reduce the consumption of short-lived plastic products by 30% by 2040 while still meeting the needs of growing populations and economies.9

Not all recycling is equal

Chemical recycling uses high heat or chemicals to break down plastic waste into base chemicals, which can then be transformed into new plastic products.10 In contrast, mechanical recycling works by sorting plastics according to material type, then washing, drying, grinding, and re-processing them into pellets that can be used for new products.11 While the latter produces 50% fewer greenhouse gas emissions per metric ton than the former,12 it currently faces challenges that hinder its widespread adoption. Plastic that is contaminated by other waste and products composed of different materials is difficult to clean and sort, and there is a lack of adequate local infrastructure and technology to collect, sort, and recycle plastic products. Mechanical recycling can be profitable, but it requires significant investment in technology and infrastructure, to the tune of roughly USD 32bn globally between 2021 and 2040.13

Extended producer responsibility systems (EPR), which assign the costs of collecting, managing, and treating plastic waste to the producer, have been found to be especially effective when coupled with economic incentives and fines. In Italy, EPR systems had a significant impact on recycling. Recycling rates for plastic packaging in Italy have increased from 37% in 2013 to 55% in 2022, the highest in the EU according to Eurostat.14

A global problem requires a global solution

Ending plastics pollution and creating a circular economy requires global partnerships. In November 2024, the UN’s Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee will meet for what is hoped to be the last time to complete negotiations regarding the legally binding Global Plastics Treaty. Reaching consensus will not be easy, but countries must be ambitious. The world needs a comprehensive plan for shifting to a circular plastics economy. Prioritizing the reduction of excessive plastic packaging, instituting design requirements that help decrease plastic consumption, and putting in place strong and fair provisions to support countries with their transition15 will be a promising start. The cost of inaction is high, but if an agreement is reached, we can mobilize a major reduction in the environmental and social costs associated with the plastics economy and its supply chain.

The author thanks the following people for their input: Mike Ryan, William Nicolle, Richard Mylles, Jackie Bauer.

For further information, please read our thought leadership disclaimer