Oliver Hart has one example he admits he might overuse but it’s a very good one. It’s about a coal mine and a power plant found next to each other. Since they’re so close, it’s efficient for the power plant to use the mine’s coal. But how can you design a contract that serves as a good basis for a long and fruitful partnership? Hart, a true specialist on the potential pitfalls of contract design, has found answers to that question and underlined how the most important transactions in an economy may not be those inside a market, but the ones that have been taken out of it.

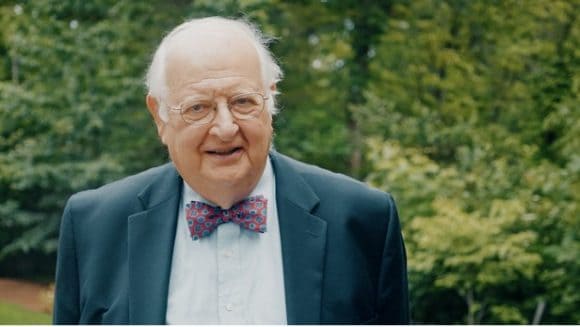

Oliver S. Hart

Oliver S. Hart

The Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel, 2016

At a glance

At a glance

Born: 1948, London, United Kingdom

Field: Microeconomics

Prize-winning work: Contract theory; theoretical tools to understand real-life contracts and potential pitfalls of contract design

Life decisions: As a student in the late 1960s, Hart decided to study economics because he liked discussing politics, but frequently lost the argument since he didn’t know anything about the world economy

Changing the world: Though he says there’s no evidence, many journalists have argued that Hart had an impact in the US government’s decision not to use private contractors for prisons anymore

Are executive bonuses justified?

Are executive bonuses justified?

It’s a sunny day on the Harvard campus and Hart, as is appropriate for a British gentleman, has chosen a dark suit for the occasion. There’s another very British custom to enjoy and that’s a nice cup of Earl Grey tea. During an enlightening conversation, he shows himself to be a composed and sincere academic, even when discussing more controversial topics such as the question of whether excessive executive bonuses are ever justified.

Can a contract ensure good behavior?

Has this question inspired you?

Get the latest Nobel perspectives delivered to you.

Hart points out how this is a question of the right incentive scheme. He explains how in many contracts, a performance-based payment is included in the hope of incentivizing for example, a CEO, to act in the company’s best interest.

“But any incentive scheme is going to have its cost, it exposes you to some risk,” says Hart. “If performance is good, you do well, if performance is bad, you don’t. It’s an active topic of debate but all measures are imperfect.”

Why employees need to have a long-term perspective

Why employees need to have a long-term perspective

The Nobel Laureate notes that there are many examples of what can go wrong with an incentive scheme. It may be that employees don’t have a long-term perspective. "You manage to make a lot of money for a time by doing things that aren’t really good, but it’s only going to become apparent later,” he explains. "Then you get out of the company, you made your fortune, and other people suffer later on when the damage is revealed."

That’s why he thinks it may be important to think about reducing bonuses and giving people a more long-term goals in their everyday work instead of “making money on the bottom line and not worrying about the bigger picture.”

Why who’s in charge is important

Can contract design anticipate what may happen in the future?

It’s a challenge to write a contract that’s supposed to last for 30 or even 50 years. “So many things can happen, in the energy sector, in the world,” he says. “Whatever we put in might no longer be appropriate.” Hart explains how this is what economists refer to as incomplete contracts. You never know what the future may hold, and that’s why parties will never be able to write a perfect contract that takes into account all future possibilities. “It’s a weakness that we can’t think that far ahead, and I’m interested in how parties get around that.”

He gets back to his favorite example of the coal mine and its power plant neighbor. "We’re now in a one-on-one situation, which can be regulated either by a contract we wrote before, or I could buy you," he says. “I’m not worried now about becoming entirely dependent on you. But a key part of my work is that there’s a downside to that.”

“Who owns things matters because the owner of any asset has residual control,” he continues. “When I become the owner of your mine, you lose power. Now, I can take advantage of you. And that’s going to lower your incentive to have efficiency-enhancing ideas.”

Public or private ownership?

Public or private ownership?

Who has residual control rights is a key question for Hart and he argues that this is also highly relevant for government work and public-private partnerships.

There are certain services an economy won’t provide at efficient levels. The question is if the government is going to finance an activity, how should it be carried out? It doesn’t have to be publicly owned.

He emphasizes how the framework of incomplete contracting provides a good way to think about this. "An ideal contract will specify everything, in complete detail, unambiguously,” he says. “The difficulty arises when things are left out of the contract, and the question then is who gets to decide?"

If, for example, governments decide to outsource the administration of their prisons, this might lead to a cutback on guards to maximize profit. “The result might be more violence,” he says. “We argued that there was a tradeoff but when it came to high-security prisons, where controlling violence is paramount, the case for public ownership was quite strong.”

While he won’t admit that the late Obama administration’s decision to not privatize prisons anymore has anything to do with his papers, but there might be some truth to it.

It’s clear that his work has had real-world impact. During the Nobel banquet speech, Hart underlined how economists can provide answers to the world’s most pressing questions. He wouldn’t lock himself up in an office delving into books without thinking about the bigger picture or topics that go far beyond things within his own expertise.

Outsourcing foreign policy

In his work, Hart also discussed government-run hospitals and schools and he argued, for example, that the privatization of garbage collection is probably a no-brainer. "In other situations, the balance might go the other way,” he says. “Could you imagine governments outsourcing foreign policy, contracting to carry out diplomacy?" Hart laughs, knowing it sounds a little crazy. "But," he continues, "the way to see it’s crazy is through an incomplete contracting framework."

Can a government outsource its foreign policy?

A new social contract for the world

A new social contract for the world

It was also during the banquet speech that he emphasized the importance of opening doors to people who are being persecuted. When he says, "it’s not America first, or Europe first, or anybody first," it’s clear how he feels about recent political movements taking place in his current home country and around the world.

We shouldn’t just be selectively putting weight on the rest of the world, we should be doing it every day of the week. That’s what I would urge young people to be thinking about.

In times of rapid technological development, in some ways Hart remains a classical economist. "Economics has a message which is, you let the market do its thing in terms of achieving efficient outcomes, and then the government is there to deal with atonalities,” he says. “This is the way it works and should work.”

Rather than doing things which will make the market less efficient, we should be focusing on the redistribution aspects. That’s something which I believe in very strongly.

What to do when new technologies start threatening our jobs

Has this question inspired you?

Get the latest Nobel perspectives delivered to you.

A rich life

A rich life

Hart knows that innovation can’t be stopped, nor should it be. He is concerned about the growing inequality but argues that politics isn’t doing anything efficient to deal with the problem. Perhaps, with the help of the world’s leading economists, change is possible.

One of the things about winning the Nobel Prize is that I may have an opportunity to do some good, one’s impact could be greater than before. I don’t want to just think about what I did for myself, my family. I would like to think, at the end of it all, there was some small way in which I improved the world. This is part of a rich life.

Why do countries have to find better ways to grow?

Hear Michael Spence's view on how countries can grow sustainably while having a long-lasting positive impact.

UBS Nobel Perspectives Webinar Series

Oliver Hart featured in our third UBS Nobel Perspectives webinar as part of the series. He joined Michael Baldinger, Head of Sustainable and Impact Investing in a webinar to discuss the implications of COVID-19 for investing in the current climate with a focus on Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) factors.

More Nobel Laureate stories

Has this question inspired you?

Get the latest Nobel Perspectives updates delivered to you.