State of the race

State of the race

A Financial Times / University of Michigan survey found Joe Biden gaining ground on the question of which candidate voters think would manage the economy better. Donald Trump still prevails 41% to 37%, but the former president’s advantage has narrowed from eleven points in February, which suggests that ebbing inflationary pressure has worked to the incumbent’s advantage. As we discuss in our section on consumer sentiment, the economy should remain a crucial factor in the outcome of this race. With less than five months before Election Day, and early voting becoming more commonplace, both candidates have fewer opportunities to convince a diminishing number of undecided voters that they merit support for a second term in office.

While there are precedents, it has been more than a century since a sitting chief executive was challenged by a predecessor in the general election.1 Neither candidate today enjoys broad support, with numerous polls suggesting that a significant number of Americans would have liked to see some fresh (and younger) faces leading the national ticket. While familiarity may breed contempt in this election, the two presumptive candidates’ policy platforms do offer voters a clear choice.

Scenario analysis

If Trump wins

A second Trump Administration would seek to extend most of the existing personal tax cuts that are scheduled to expire at the end of 2025. To the extent Republicans control both chambers of Congress next year, those cuts would almost certainly persist. The former president also has expressed interest in reducing the corporate tax rate further but has been inconsistent on his preferred tax rate, and the cost to the US Treasury makes an additional cut less certain. However, if Democrats control the House, they hold an important advantage in negotiations with Trump because a failure to act on a tax bill would trigger a resumption of higher marginal tax rates. In that scenario the two political parties will be compelled to negotiate, with the likely result being an extension of low tax rates for the less affluent.

Trump has repeatedly expressed his support for tariffs, viewing them as opportunities to leverage concessions from adversaries and allies alike. Based on action taken in his first administration, we accept higher tariffs as a given. While their imposition does raise revenue for the Treasury, it comes at the cost of renewed inflationary pressure and geopolitical friction. The consumer discretionary sector is exposed in that environment. However, a more lenient regulatory posture would benefit the legacy energy and financial sectors. Trump is also likely to scale back the “all-of-government“ emphasis on sustainability initiatives and restrain the Environmental Protection Agency from new initiatives on climate change.

If Biden wins

A Biden Administration would attempt to raise taxes on more affluent Americans. However, the ability to do so is likely to be constrained by a Republican Senate, which again leads us to a compromise on taxes. We believe Biden would be obliged to rely on executive actions to institute policies designed to counter the impact of climate change. A more stringent regulatory regime would be promoted, but recent US Supreme Court decisions to limit the prerogatives of federal agencies could restrain the scope of implementation without explicit support of Congress.

We do not expect either candidate’s second administration to focus on the escalating federal deficit, although both political parties will express an abstract ambition of confronting it at some point in the future. Geopolitical tension will likely protect the Pentagon from significant expenditure reductions, while popular support for entitlements makes Social Security and Medicare beneficiary cuts highly problematic.

As we have reminded our readers in prior editions of our ElectionWatch series, the composition of Congress is a critical component in assessing the likelihood that any policy will be implemented. This is especially true for fiscal and social policy, where the role of Congress cannot be ignored. However, in foreign policy, US presidents have fewer institutional constraints. As a transactional isolationist, Donald Trump is skeptical of foreign entanglements and prefers bilateral negotiations over joint action. By contrast, Joe Biden has an abiding desire to preserve the transatlantic alliance and prefers to leverage traditional institutions to promote US interests.

Our initial assessment of the likely outcome of the 2024 presidential and congressional elections is set forth below. We see four likely scenarios, with a Republican Senate being the most likely outcome. Biden and Trump are within striking distance of the other. Absent a dramatic faux pas by either candidate, the race will come down to the wire. We will update our probabilities in the months ahead.

Swing states in the 2024 race

President Biden faces a challenging re-election contest. There are seven states pivotal to the outcome of this election. All seven are considered “swing states,” whose electoral votes have been actively contested in recent presidential elections. Some of these states, such as Arizona and North Carolina, have a predisposition to vote Republican in presidential races. Others, such as Pennsylvania and Michigan, generally opt for Democrats. But each one will be a critical battleground for Biden and former President Trump.

Arizona

11 electoral votes

With two exceptions (1996 and 2020), Arizona voters have supported GOP candidates for president since 1952. The state’s rapid population growth has made it more competitive for Democrats, but Trump still enjoys a 4- to 5-point advantage in recent polls. Immigration and inflation are critical issues for voters.

Georgia

16 electoral votes

Biden has narrowed the gap, but Trump still holds a sizable lead in recent polls. The state of the US economy was the most critical issue for voters in a recent Quinnipiac University poll, which shows Trump running ahead Biden despite the former president’s recent felony conviction.

Michigan

15 electoral votes

We do not believe Joe Biden can win reelection without Michigan. The race is currently a dead heat between the two presumptive nominees. The Biden campaign plans to invest heavily in local campaign offices and rely on popular Governor Gretchen Whitmer to barnstorm on his behalf.

Nevada

6 electoral votes

Trump holds a commanding lead in recent polls. The leisure and hospitality industry constitutes more than one-quarter of all jobs in Nevada, and many voters are members of the powerful Culinary Workers Union. The former president’s proposal to eliminate taxes on gratuities may resonate among the voting public.

North Carolina

16 electoral votes

Trump holds a commanding lead, which poses a significant challenge for Biden as he led in polls in 2020 but still lost, suggesting that he underperformed on Election Day. Neither candidate approaches 50%; roughly 8% of poll respondents prefer third-party candidate Robert F Kennedy, Jr.

Pennsylvania

19 electoral votes

Recent polls show Trump and Biden locked in a remarkably close contest, with one candidate or the other holding a narrow lead. In a reflection of the state’s importance, Biden has opened 24 separate campaign offices. The Trump campaign also opened its first office in the state.

Wisconsin

10 electoral votes

The polls show one candidate or the other within the margin of error. Trump plans to focus on immigration and border security, while Biden will likely focus on reproductive rights and the social safety net. Senator Tammy Baldwin (D) is running well ahead of President Biden in her re-election race for the Senate.

Political pessimism punishes performance

The perceived health of the economy has been a deciding factor in the outcome of US elections for generations. While other policy issues are consequential—immigration and reproductive rights are front and center this year, for example—history suggests that presidential contests are often decided on whether one candidate or the other is able to convince voters that they are attuned to their daily financial challenges. Incumbent politicians have a vested interest in focusing on the strengths of the economy, while opponents are apt to highlight its shortcomings.

In the world of presidential politics, perception matters. Despite a resilient labor force, ebbing inflation, and a surging stock market, consumer sentiment remains subdued. We believe there are two principal reasons for the variance.

First, consumers’ inflation perceptions were anchored to pre-pandemic levels rather than the year-over-year inflation rate analysis that economists favor. After two decades of modest price increases, the 8% rate of inflation in 2022 was a shock to the system, and prices are now 20% higher than they were in early 2020.

We are all susceptible to recency bias and salience bias, whereby we place greater emphasis on recent events that are easily remembered. The result is that the adverse impact of inflation on consumer sentiment tends to lag the real economy at a rate of roughly 50% per year.2

Second, partisan bias plays a role in how voters interpret economic data. Look no further than polling done by both the Gallup Foundation and the Kaiser Family Foundation in 2020. When Gallup asked respondents to name the biggest problem facing the US in August of that year, the global pandemic topped the list. The health of the economy trailed far behind. But when Kaiser asked respondents to identify one issue that was most important in choosing a president, the economy ranked highest. Drilling down a bit further, Gallup asked about Americans’ views of the economy. There was a 51% spread between how Democrats and Republicans responded to the question.3

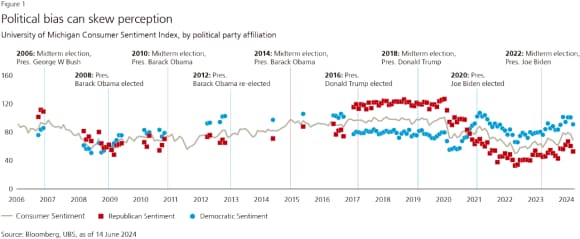

The University of Michigan’s Index of Consumer Sentiment measures how Americans feel about the economy and their own personal financial conditions. The survey also breaks down the information by the respondents’ political affiliation. As we show in Fig. 1, sentiment among Republicans and Democrats often follows US political outcomes, with Americans feeling more confident when their party has political power, and more fearful when the opposing party is in control. This effect has been especially strong after presidential elections where the White House has changed from one party to the other (e.g., 2008, 2016, and 2020).

The cost of the partisan divide

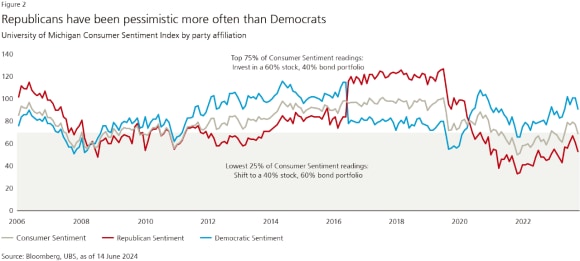

All of which leads us to ask: how much does a partisan perspective actually cost investors over a longer period of time? To answer this question, we decided to model an investment strategy that is based on the University of Michigan Consumer Sentiment Index, from September 2006 to May 2024. The investment strategy follows these simple rules:

- When the sentiment index (either at the index level, or broken down by party affiliation) reflects an optimistic or neutral view of the economy, we assume that investors are invested in a 60% stock, 40% bond portfolio.

- Conversely, when the sentiment index reflects a pessimistic view of the economy (e.g., the party-affiliated index falls in the lowest 25% of Consumer Sentiment index readings), we assume that investors shift to a 40% stock, 60% bond portfolio.

While the framework is admittedly rather basic, it incorporates the results of prior academic research, which shows that investors disappointed with the outcome of an election often adopt a “risk-off” strategy and take refuge in fixed income securities.4

Based on the rules of our simple investment strategy, pessimistic investors would have been more defensively positioned for the early days of the post-Global Financial Crisis rebound (a period that saw the European debt crisis, several “flash crash” market selloffs, and fears over a double-dip recession). A similar effect would have taken hold in 2017 when enthusiasm for tax cuts contributed to an equity market rally, so those adopting a risk-off strategy upon the election of Donald Trump would not have fared as well as optimistic investors who retained a preference to equities. Pessimism would also have been costly for investors over the last two years, during which stocks have generally provided solid returns.

Altogether, trading based on the Consumer Sentiment index itself would have cost investors about 0.2% per year versus a buy-and-hold investor. This “pessimism penalty” would have been even larger—0.9% per year (57% cumulatively from 2006 to 2024)—for investors who traded their portfolios based on the Consumer Sentiment reading of whichever party was out of power at the time.

Political loss aversion

These examples are consistent with the political theory of “negative partisanship,” which describes US politics as increasingly partisan (no surprise), but also observes that Americans tend to feel more negatively about the other party than they feel positively about their own. This concept is a parallel to the behavioral bias known as “loss aversion,” which observes that investors tend to feel about twice as much pain from losses as they feel pleasure from gains. In this case, we are experiencing loss aversion from electoral outcomes, rather than investment returns. In short, we tend to view the other political party’s ideas as much more dangerous and damaging, which can lead us to overreact in response to political disappointment.

This partisan perspective is a dangerous element for investors, especially in a politically charged election year, threatening to override one’s objective assessment of risk and potentially dangerously skewing our investment behavior. The 2024 election will be consequential, but US political outcomes are far from the largest drivers of global economic growth and financial market returns. Regardless of which party wins the White House, many of the policy outcomes will also depend upon which parties control the legislative branch, and the size of their controlling majorities. Some equity sectors, such as energy and information technology, are more exposed than others to changes arising from executive action. But it’s equally important to remember that well-constructed financial plans are able to withstand periodic political upheaval.

Monetary policy in a polarized political environment

The vaunted independence of the US Federal Reserve has been subjected to more scrutiny than usual in recent months. The attention ratcheted higher after the Wall Street Journal reported that advisors to former president Donald Trump were drafting proposals to erode the central bank’s unilateral authority over monetary policy if he is elected again in November.5 The ensuing media coverage prompted some investors to inquire whether the conduct of monetary policy will shift to the executive branch.

In short, while criticism over the Fed’s handling of monetary policy almost certainly would increase in a second Trump Administration, we do not believe a substantive shift in responsibility to the executive branch is likely.

First and foremost, it is important to remember that the Fed has often been subjected to criticism from elected officials seeking easier money and lower interest rates. Presidents Truman, Johnson, and Nixon were anxious to impose their own views regarding interest rates on the Fed, with varying degrees of success. In that context, former President Trump’s avowed desire for greater influence over monetary policy is not a new phenomenon.

While the Federal Reserve is a creature of Congress and the latter is free to alter the central bank’s mandate, there has not been much appetite to move beyond incremental legislative changes. Congress did enter the fray in 1978 with the enactment of the Full Employment and Training Act (i.e., the Humphrey Hawkins Act). The legislation mandated periodic reports to Congress and instructed the Fed to pursue policies that would promote both price stability and full employment as a dual mandate. But Congress deliberately stopped short of mandating deference to either the executive or legislative branches of government in the daily conduct of monetary policy.

Second, any attempt by a future president to alter the composition of the Federal Reserve’s Board of Governors faces statutory obstacles. Once confirmed by the Senate, members of the Fed’s Board of Governors serve 14-year terms and may be removed only “for cause.” While the definition of “cause” is reasonably vague, policy differences are unlikely to engender much sympathy from the judiciary absent an amendment to the Federal Reserve Act.

There is more ambiguity as to whether a president can designate a new individual to serve as chair of the Board of Governors. But this too faces obstacles as an open seat on the Board must be available for presidential appointment or another governor would have to accept the role. Removing the current chair for cause or designating another individual to serve as chair also might not result in an abrupt pivot in monetary policy. The lengthy term of the seven Fed governors (14 years) and the rotating membership of regional Fed presidents (five of whom vote on policy at any one time) on the FOMC are specifically designed to insulate the policy-setting body from direct executive control. Jerome Powell’s term as the chair expires in May 2026, so the simplest path for a new president inundated with numerous other policy decisions would be to wait until Powell either retires or resigns under pressure and then appoint another individual more aligned with the executive’s policy preferences.6

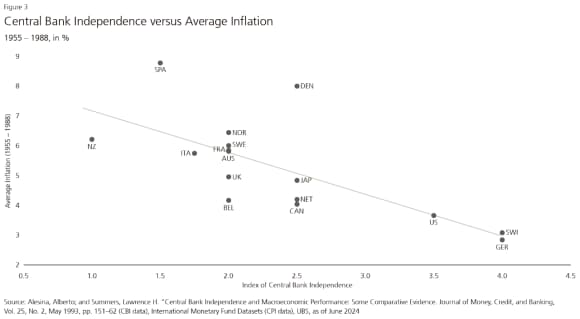

Third, overt political interference in the execution of monetary policy would most likely trigger an adverse and counterproductive market reaction. Central bank autonomy is a prized attribute of developed economies, occasionally undermined in practice, but always preferred over interference by elected officials motivated by their prospects for re-election. Easier monetary policies to promote employment at the expense of price stability often result in higher levels of inflation (see Fig. 3). In the unlikely event that overt political interference rises significantly and legislative changes are deliberated in a serious manner, we would expect investors to seek refuge in gold and inflation-protected securities.

The US Federal Reserve’s reputation was tarnished by a delay in responding to incipient inflationary pressure in 2021. However, there is little appetite among institutional investors to abandon a bifurcated system where the Fed manages monetary policy with a high degree of autonomy and leaves fiscal policy to Congress. Equally important, any effort to alter that division of responsibilities will face opposition in the US Senate, whose consent is necessary for any change in the law and whose membership is more likely to resist an explicit transfer of responsibilities to the Oval Office.

Endnotes

Endnotes