Technology transforms the transplantation process

How can technology facilitate the organ transplantation process and help save people’s lives?

![]()

header.search.error

How can technology facilitate the organ transplantation process and help save people’s lives?

Patients who need an organ transplant usually have to wait long for the live-saving procedure. And time is a luxury they cannot afford. They are put on waiting lists while their health continues to deteriorate. Several solutions have been proposed to shorten the waiting time for transplant patients and make more organs available, including a move from explicit to presumed consent (a new opt-out system). Yet, there are still not enough donors or organs viable for donation.

How can technology facilitate the organ transplantation process and help save people’s lives?

More than 103,000 patients are waiting for an organ transplant in the US alone

Organ donation and transplantation is a surgical process during which a failing organ is replaced with a healthy one. Organ recipients are usually patients who are critically ill in the end stages of organ failure. Undergoing an organ transplant can prolong a person’s life, giving those with a chronic disease a chance to reach the average lifespan.

"Many people need an organ transplant due to a genetic condition such as polycystic kidney disease, cystic fibrosis, or a heart defect. Infections such as hepatitis, physical injuries to organs, and damage due to chronic conditions such as diabetes may also cause a person to require a transplant.” 1

According to preliminary data from United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS), which serves as the national Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network under federal contract, 42,887 organ transplants were performed in the US in 2022 – an increase of 3.7% from 2021 and a new annual record.2 Impressive as this number may seem, it accounts for less than half of the people who still need organ transplants.

In the US alone, more than 103,000 people are currently on organ transplant waiting lists and every day 17 of them die waiting for an organ transplant.3

Thousands of donated organs go unused, costing lives

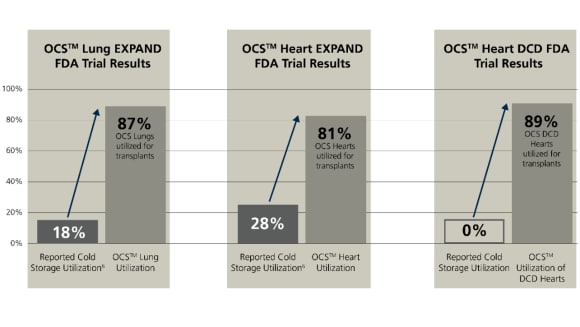

Every year, thousands of donated organs go to waste, particularly lungs, hearts, and livers (see Figure 1). On top of the scarcity of viable organs, not all donated organs are utilized – further exacerbating the problem of availability. Why do they go to waste?

There are two main types of organ donations from recently deceased patients: donation after brain death (DBD) and donation after circulatory death (DCD). Traditionally, donation after brain death is more common than donation after circulatory death, since the quality of organs obtained after circulatory death can, at times, be difficult to assess.4

Although more and more donors are registered in the system, the percentage of utilized organs is very low. As a result, the organ shortage and the recipient waiting lists will likely persist.Traditionally, when in doubt, a surgeon would rather reject an organ ahead of the procedure rather than just before the transplantation if they are not confident about its viability, since any transplant complications adversely affect their statistics. This may happen when an organ has been obtained after circulatory death. Since it may be difficult to assess the quality of such an organ, it is often discarded at some stage of the transplantation process.

Organ Care System to optimize organ transportation

Hypothermia remains one of the most common ways of preserving donated organs. Donated organs are transported to a recipient for transplant stored in organ-preservation fluid, cooled with ice, and transported in a cooler. However, this method is not ideal because the transported organ can suffer damage and it may be difficult to assess its viability prior to transplantation.

Here is where technology can help. The Organ Care System (OCS) is a medical device that allows donated organs, including heart, lung, or liver, to be kept in a metabolically active state. It not only keeps the organ in much better condition as time passes, which makes it viable for longer, but it also allows for the organ viability assessment just before the transplantation, thus increasing the chances for the success of the procedure.

Promising results of clinical trials led to broad FDA label

Before the OCS was approved for broad use, it had to be evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). FDA approval means that data on the effects of using a given drug or equipment have been reviewed and are a proof that the benefits of using the drug or equipment outweigh their known and potential risks. Clinical evidence is necessary to support the claim. Without hard data and FDA approval, it is highly unlikely that transplant centers would change their current practices and start using the OCS.

OCSTM Lung | OCSTM Lung | OCSTM Heart | OCSTM Heart | OCSTM Liver | OCSTM Liver |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

OCSTM Lung | Clinical Outcomes | OCSTM Heart | Clinical Outcomes | OCSTM Liver | Clinical Outcomes |

OCSTM Lung | 87% | OCSTM Heart | 81% | OCSTM Liver | 2x |

OCSTM Lung | 50% | OCSTM Heart | 65% | OCSTM Liver | 43% |

Clinical tests conducted with the use of OCS provided very promising results: the utilization of lungs and hearts exceeded 80%, while severe posttransplant complications were reduced by 50% and 65% for lungs and hearts respectively. The utilization of donor livers doubled, with a 43% reduction of severe posttransplant complications. Every organ wasted is a life not saved – by increasing the percentage of utilized organs, the OCS can give more patients a chance for a transplant that may save their lives. As a result of the clinical trials, the FDA approved the OCS for use, thus helping to transform the transplantation process.

Technology is transforming organ transplantation

While numerous healthcare technologies are still in the developmental stage, the OCS is already used more and more broadly, helping to transform the organ donation and transplantation system. More organs available for transplantation means shorter wait time for patients and better planning and more efficient work for doctors.

CFA, Senior portfolio manager, Thematic Equities

Thomas Amrein (MSc, CFA), Director, is a Senior Portfolio Manager and Lead Manager of the Digital Health Equity strategy. Before that, he focused on the US healthcare sector, managing the USA Growth Opportunities Equity strategy. He became Lead Portfolio Manager of the Credit Suisse Global Biotech Innovators Equity strategy in 2016. Thomas joined Credit Suisse Asset Management, now part of UBS Group, in 1996. He has covered the healthcare and other sectors for over 20 years. Thomas holds a master’s degree in Business Administration from the University of St. Gallen and is a CFA charterholder. He also attended postgraduate courses in biotechnology at the University of Basel and ETH Zurich.