The investor’s dilemma

The art and science of valuing hyper-growth companies

![]()

header.search.error

The art and science of valuing hyper-growth companies

Companies that disrupt a market or industry are fiendishly hard to value. Peter (Pete) Bye and Albert Tsuei walk us through how they approach valuing both early-stage and incumbent companies in disruptive settings.

When Clayton Christensen first coined the term ‘The Innovator’s Dilemma’1 he surely did not foresee the breadth, depth and overall impact it would have as a cornerstone of business development. Whether consciously or otherwise, few corporate leaders are untouched by the power of his ideas.

Christensen’s thinking not only stands the test of time, but also is highly relevant to investors. By definition, disruptive companies tend to defy convention and test the outer limits of valuation models. In the face of such uncertainty, traditional techniques frequently buckle.

How disruptive innovation enters the market

The 2024 UBS Global Investment Returns Yearbook reminds us of the transformative (and often transient) nature of business by underscoring how a “high proportion of today’s companies come from industries that were small or non-existent in 1900.” Indeed, you only need look at the top ten global companies by market capitalization on a rolling ten-year basis to see the revolving door access to the winner’s circle.

Disruption is rife and the commercial landscape nasty and brutish. To ward off disruptive innovations, incumbent firms therefore need to either completely disrupt themselves, acquire a disruptor, or spin off operations and allow competing realities to co-exist under one roof until the future becomes clearer.

Self-disruption is hard. Status-quo bias, the risk of sacrificing existing revenue streams, investment costs, organizational silos and cultural issues all conspire against decisive action.

Self-disruption is hard. Status-quo bias, the risk of sacrificing existing revenue streams, investment costs, organizational silos and cultural issues all conspire against decisive action.

With all investing, a gap exists between price and value. Markets are not perfectly efficient, thereby allowing for alpha opportunities to emerge.

Indeed, in his autobiography My Life as a Quant, Emanuel Derman wrote of his mentor Fischer Black, In one short essay he struck at the foundation of financial economics.” Black essentially wrote that “certain economic quantities are so hard to estimate that I call them unobservables,” and went on to say, “Our estimates of expected return are so poor they are almost laughable.” This is not a trivial admission; it comes from one of the founding fathers of risk management and strikes at the very heart of traditional investment principles (i.e., the Capital Asset Pricing Models, Efficient Market Hypothesis, Black-Scholes-Merton derivative formula).

This is the point at which financial theory and practice diverge – and spectacularly so. As there is currently no real Black-Scholes-Merton formula capable of capturing all the qualitative variables, baking in some flexibility (‘margin of safety’) on valuation decisions seems wise. Doing so helps to ensure buy/sell decisions are not solely based on the discount rate applied to any given model, particularly when analyzing potential disruptors and innovators.

The above is a stylized depiction of this valuation gap. Disruptive forces only cause it to grow wider, as do lower market capitalizations. Whether looking at an early-stage disruptor (i.e., harder to invest in and access), or an incumbent investing heavily behind a pivoted strategy, the investment signals are usually weak at best and distinguishing them from the noise takes expertise and skill.

There are two parts to this equation. First, you need to be mentally flexible enough to embrace the art of the possible; you need to suspend judgement and allow your imagination to kick in. It is a highly creative endeavor and requires a latticework of different mental models, modes of thinking and reference points. Second, you then need to ground this thinking in ‘real’ fundamental numbers – such as a discounted cashflow (DCF) model. It is part art, part science.

Both sides of this process really matter. If you only focus on the hard numbers, as ‘value’ investors typically do, you can miss the true potential of the upside scenario. Limited financial disclosure, negative earnings and other potential uncertainties make DCF valuations of disruptive companies rather challenging. As Lijing Zhang of Copenhagen Business School stated, “DCF is not capable of capturing all the future cash flows of a disruptor. Because analysts can only estimate the cashflow growth from existing products and services. Disruptor’s source of cash flows can change dramatically once its business model changes.”2 Simply put, DCF analysis was not designed to capture values not yet observable in operating activities.

But equally, if you only rely on the blue sky thinking you can lose sight of reality. Scenario analysis based on weighing up the various options is therefore a fundamental part of our approach. This is sometimes referred to as a ‘real-options approach’. It essentially tries to capture the part of value which is outside of a given business model.3 With these option values in mind, we ask ourselves ‘what could go wildly right?’ as keeping an eye on the upside is something routinely undervalued and overlooked by investors. Instead, risk management tends to exclusively focus on the downside and misses the opportunity cost. This is where much of the equity mispricing often happens, especially in growth companies. Thanks to the asymmetry in downside and upside outcomes and contrary to fixed income investing, the biggest mistakes in investing are around the ones that got away, not the ones that turned out to be zeroes.

For incumbents trying to disrupt themselves or enter new markets, you can blend this options approach with a more traditional valuation method (such as DCF) to also capture the intrinsic value inside the current business model. We therefore always try to heed the advice of legendary economist John Maynard Keynes who said, “It is better to be roughly right, than precisely wrong.”4

Most valuation techniques have a linear modelling bias.

Most valuation techniques have a linear modelling bias (e.g., CAGR) and do not leave room for exponentials. In a networked age, where platforms scale-up in a winner-takes-all fashion, the tipping point between success and failure can be hard to pinpoint. But once through the viability and then profitability thresholds (often achieved as much through powerful storytelling as anything else), a business can fly.

Growth investors seeking to value potential not yet captured by operating activities are, in our view, best served by seeking “directional correctness” over precision, as the magnitude of inflection for companies that have successfully navigated these forces to unlock as-yet-undiscovered whitespace dwarfs the marginal gains of quantitatively narrowing a confidence interval on paper.

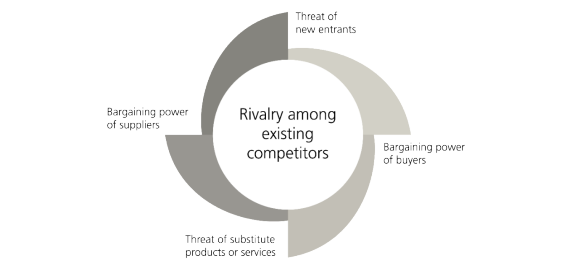

Our internal research therefore focuses on understanding the duration of a company’s competitive advantage and the capital return potential of that investment relative to other opportunities available in our universe. Our process begins with Michael Porter’s Five Forces and SWOT analysis, which we augment with frameworks derived from resource advantage theory.

Porter’s Five Forces model offers a framework for understanding the competitive pressures – and opportunities – at work in an industry. The ‘forces’ drive the way economic value is divided among companies and, perhaps even more importantly, provide a model for the challenges and opportunities faced by a potential disruptor.

They also emphasize and animate creative thinking, forcing disciplined investors to consider industry dynamics that may be underappreciated by consensus (and linear) thinking.

Industry structure is iterative, with buyers and suppliers becoming more or less powerful over time. Advances in technology can make new entrants and substitution a foregone conclusion – or, conversely, may suggest an ever-widening moat around an incumbent’s competitive position. Regulation, pricing, and distribution also play a role in the evolution of competitive dynamics.

Let’s take Uber as an example. Today, Uber has a USD 135 billion market capitalization5 and reported gross bookings of USD 162.3 billion last year.6 Despite those numbers, bookings are expected to grow in the high-teens annually into the latter half of the decade, led by annual growth in mobility bookings in the mid-20% range. However, the power of Uber’s service was underestimated for years, even by its own investors.

In 2014, the company closed a fundraising round that valued the company at USD 17 billion7 – a large increase from its 2013 valuation of USD 3.5 billion. With the benefit of hindsight, we can see a quadrupling of Uber’s valuation a year later still represented a vast discount to what the company has become. What was the reason for scepticism, and why did some potential investors see the company as overvalued? The answer lies in the disruption that Uber (and rideshare in general), provided as a service.

The mistake made by investors was not realizing that Uber’s total addressable market (TAM) was beyond that of just a taxi service.

The mistake made by investors was not realizing that Uber’s total addressable market (TAM) was beyond that of just a taxi service. In 2014, the taxi market was just over USD 10 billion in the US, according to IBISWorld. Uber doesn’t disclose its mobility gross bookings from the US, but we know that it generates around half of its revenue from the country.8 If we apply that number to its USD 68 billion of mobility bookings in 20239, Uber would be over 300% than the 2014 market – it has become more than just a taxi service.

Uber’s service addresses far more than just the taxi or limousine market; rather, we think it should be viewed as a new form of travel itself. Americans drove more than three trillion miles in 20239– at a price of a few dollars/mile, suggesting Uber’s real TAM is in the trillions of dollars. Instead of just competing with a small taxi market, Uber competes with all forms of transportation from your morning commute to car ownership. AAA estimates that it cost USD 12,000 to own a car in 20239 – with an average Uber price of around USD 20 in the US, this would represent almost 600 Uber rides per year.

While Uber won’t be able to capture all of this as bookings or revenues, our view is that comparisons to the dawn of air travel are more apt.

This would suggest Uber still has a considerable runway ahead of it. For example, passengers in the US airline industry grew at a compounded annual growth rate of approximately 9% from 1958-1977 as air travel became deregulated.10 This type of growth ramp by the aerospace industry (itself a disruptor) is seemingly being modelled by Uber’s active user growth: high teens in Q1, despite a 150 million base of users.

A combination of sustained user growth, increases in user frequency as new products are added, and a ramping ad business that supplements profitability lead us to believe that Uber can drive bookings growth in the teens through the end of the decade. While the company trades at around 20 times next-twelve-months EV/EBITDA,11 its future earnings could make this multiple look cheap. If we look at the 2014 valuation on 2023’s EBITDA, Uber was valued at just over three times EV/EBITDA.

This is precisely why we use DCFs to gain a greater understanding of the future value of disruptive companies. However, although DCFs are valuable, they limit future projections of a company’s performance to its current business; Uber did not have a food delivery business until August of 2014 and in 2023 Uber Eats recorded just over USD 60 billion in bookings.6

Classic measures of valuation must therefore be partnered with a qualitative analysis on the potential for expansion into new areas. With a user base of 150 million people and over 6 million drivers,6 Uber could introduce highly successful businesses that we have not even considered. It is our job as analysts to combine both the quantitative numbers with a qualitative assessment of a company’s potential for future growth.

Ultimately, elite-growth companies are marked by the ability to disrupt large existing markets, or pioneer new ones, often at underestimated penetration rates. Sizing both the TAM, and careful modelling under realistic S-shaped adoption curves,12 can drive upside returns vs. consensus; usually reflected in expected value weighted towards the out years of a DCF framework and/or beyond the typical forecasting period.

As we have seen, hyper-growth companies also often have platform attributes, with the capacity to address additional, large TAMs that aren't captured in the initial modelling and scenarios. These can become more concrete 2-3 or 5-10 years into an ownership period and enable sizable further upside to be modelled within a valuation framework.

For us, valuation is driven by both the probability we assign to different operating scenarios, and how we believe investors will assess, growth and risk profile of the company. Incorporating our forecasts into a 10-year DCF model, we try to think about discount and terminal growth rates in ways that reflect our expectation of change in market consensus.

Disruption does create uncertainty but, more importantly, it changes the underlying structure of businesses and entire economies.

Much as we would like to believe otherwise, disruption is neither new nor novel. It is part of how economies evolve and change. Disruption does create uncertainty but, more importantly, it changes the underlying structure of businesses and entire economies. Those structural changes imply investing, valuing or managing companies on the assumption mean reversion always works and mechanical models/metrics are the answer is dangerous. As such, valuing hyper-growth stocks will always be a blend of art and science.

Investing through change

An exploration of disruptive and innovative forces shaping economies and markets.