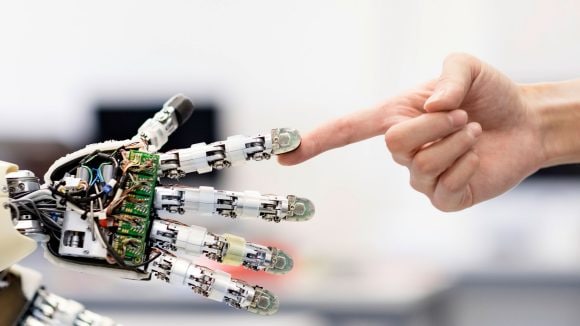

What jobs can human beings do that robots cannot?

The idea of robots taking our jobs isn’t new, but as AI becomes more advanced, and more tasks can be automated, economists are asking if there are any jobs that robots cannot do, and if there is room for humans in the future workforce.