A rich history

A rich history

Château Wolfsberg stands proudly on an elevated, north-facing plateau between the Lower Lake of Constance and the Thur Valley. Although it is one of the younger and more modest of the castles in the vicinity of Lake Constance, Wolfsberg boasts an extraordinarily rich and eventful history, which reached its peak under the Bonapartists in the 1820s and 30s.

A range of roles

A range of roles

From a luxurious summer residence through to Thurgau's first guest house, a model farm, and a spa hotel – Wolfsberg was used for a variety of different purposes before it became home to the UBS Center for Education and Dialogue. The different owners over the years were just as diverse.

History of the château’s owners and its construction

History of the château’s owners and its construction

Wolf Walter von Gryffenberg

Wolf Walter von Gryffenberg

The name «Wolfsberg» originates from the château's first owner Wolf Walter von Gryffenberg, who came from a family of patricians named Werli, Weerli, Wehrli, or Wehrlin (variants of Werner). They had been established in Frauenfeld since start of the 16th century.

In the spring of 1570, Wolf Walter's name appeared as the buyer of the Lanterswilen farm, located between Ermatingen and Château Wolfsberg, which was first documented in 1272 under the name «Landrehtiswiller» and still exists today.

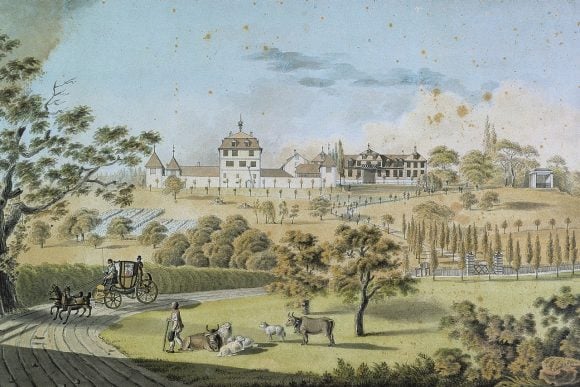

The newly acquired residence evidently didn't satisfy Wolf Walter's requirements for very long. In 1573, he purchased a plot of land called “an der Halden,” which was owned by the municipal authorities. A dendrochronological analysis of the château's cellar beams revealed that Wolf Walter built his new residence, which he named «Wolfsberg», in this prominent position in 1576. According to old sources containing images that have since been lost, it is said to have been a half-timbered construction with tall stepped gables. Wolf Walter had barns and stables, a wine press, and a brick kiln built next to the main dwelling.

An unexpected issue then arose: he had to buy the timber for the new buildings himself, as the municipal authorities refused to do so on the grounds that any buildings outside of the Lanterswilen farm were not eligible for receiving municipal funds. In general, Wolfsberg and its founder didn't have much luck: as well as having several disputes with the authorities in Ermatingen, Wolf Walter also fell out with the previous owner of the Lanterswilen farm over an unpaid debt. Feldbach Monastery also took legal action against him for allegedly letting his property fall into disrepair and not paying the interest on time. All of these disputes, most of which he lost in court, forced the financially troubled Junker to sell the property.

The Gelderich von Sigmarshofen family and their successors

The Gelderich von Sigmarshofen family and their successors

In 1595, Friedrich Gelderich von Sigmarshofen acquired the château. The Gelderich family came from Ravensburg and were raised to nobility in 1559 by Emperor Ferdinand I. The new owner seemed to be a little more fortunate than his predecessor: he extended the property through substantial land acquisitions and on July 6, 1595, he received lower jurisdiction within the château area from the Old Swiss Confederacy. This meant that Wolfsberg would be one of Thurgau's Freisitze (farmsteads that were exempt from duties and taxes) for the next 200 years until the end of the feudal era. The owner automatically became a member of the Manorial court, but had no rights to vote at its sessions, since the Freisitz had no vassals.

The Gelderich were keen protestants and supported education for the rural population. In 1614, their donation of 500 guilders laid the foundations for an evangelical school in Ermatingen.

In 1701, Château Wolfsberg passed to Duke Leopold Eberhard von Württemberg, the ruling Prince of Mömpelgard (the county of Montbéliard), who promptly gave it to his wife Anna Sabina Hedwiger. Soon afterwards, Anna Sabina Hedwiger was raised to the hereditary status of imperial countess by Emperor Leopold I, and was given the title «Countess of Sponeck».

Johannes Zollikofer von und zu Altenklingen (1731–1759) and Hartmann Friedrich von Breitenlandenberg (1759–1795)

Johannes Zollikofer von und zu Altenklingen (1731–1759) and Hartmann Friedrich von Breitenlandenberg (1759–1795)

In 1731, the Freisitz was passed from princely ownership to a respected patrician dynasty, the well-known St. Gall merchant family of Zollikofer. Their ancestral seat in Altenklingen near Märstetten, Thurgau, was built in 1586 and is still owned by the family today.

The new owner of the château, Junker Johannes Zollikofer von Altenklingen, immediately set about extensively renovating Wolfsberg, which had hardly been altered since it was built, and adapted it to meet the living requirements of the times. As a result, the stately building as we know it today started taking shape in the early 1730s. It is likely that, during this time, the château was given an outer wall with corner towers, and that Johannes Zollikofer also initiated the construction of the «Bernese House». The wall was gradually removed by subsequent owners. This half-timbered building with a pergola facing the courtyard was erected a few steps to the west of the château and was demolished in 1889.

In addition, the owner of the château marked out his area of jurisdiction using boundary stones. These markers were inscribed with the letters WZ (Wolfsberg/Zollikofer) and the year 1732. Pieces of brick and broken glass were laid underneath to make the boundary more prominent. The Junker, who was the first person in Ermatingen to own a carriage, paid for the often impassable access roads to be leveled out and had drainage ditches installed.

After the death of his wife Elisabetha Allemand, in 1759, Johannes Zollikofer sold the Freisitz to Hartmann Friedrich von Breitenlandenberg, who owned the château for almost 30 years.

Jean Jacques Högger (1795–1815) and Ignaz von Wechingen (1815–1824)

Jean Jacques Högger (1795–1815) and Ignaz von Wechingen (1815–1824)

In 1795, the wealthy Baron Jean Jacques Högger, a banker and merchant from Amsterdam, acquired the estate. The imperial Russian Councillor of State, who was highly regarded in business circles, used Wolfsberg as a summer residence, spending the winter in Munich.

Around 1797, he had the new château (now called the «Parquin House») built to the south-west of the existing building. It was intended as guest accommodation and included a riding hall in the central part. Although the feudal system had come to an end around a decade earlier and Wolfsberg was no longer a Freisitz, the grand estate experienced a period of splendor under Jean Jacques Högger's ownership. According to guest books and contemporary press reports, the château owner hosted numerous well-known figures. These even included Bavarian King Maximilian I, who visited Wolfsberg in July 1811 with a large entourage, as well as young composer Carl Maria von Weber (1786–1826), who spent several days there in August of the same year.

When Jean Jacques Högger passed away in 1812, his daughter Juliane Wilhelmine inherited the château. Three years later, she sold it to Baron Ignaz von Wechingen from Feldkirch, who came from a modest background and had amassed a degree of wealth as an English officer in the campaigns against Napoleon I.

Charles Parquin

Charles Parquin

In 1824, Wolfsberg passed from the possession of a sworn opponent of Napoleon I into the hands of a keen supporter of the Emperor: Charles Parquin. After the defeat at Waterloo in 1815, the overthrown Emperor Napoleon I was forced into exile. His relatives also fled the country, and among them was Hortense de Beauharnais (1783–1837), the daughter from Empress Joséphine's first marriage and the wife of one of his brothers, Louis, whom he had made King of Holland.

In 1817, Hortense de Beauharnais sought exile in Switzerland and acquired Château Arenenberg near Mannenbach, Thurgau. There, she hosted numerous relatives and supporters of the emperor, including Charles Parquin, who, as an ardent admirer of Napoleon, had risen in rank (and proudly acquired a number of wounds) during numerous battles.

In 1824, Parquin had the opportunity to purchase nearby Wolfsberg from the von Wechingschen heirs, having married Louise Cochelet, a confidante and companion of Queen Hortense, two years earlier.

Château Wolsberg as a guest house

The close ties to Château Arenenberg, where a growing number of guests from nearby countries used to stay, may have prompted Parquin to convert the new château into Thurgau's first guest house. Inspired by Château Arenenberg, he had part of the former riding hall converted into a tent room and had the guest rooms fitted with all the modern comforts of the time.

Picturesque spots were created in the extensive grounds and a pavilion was erected, affording great views. A small log cabin called the «Eremitage» was also built in a secluded spot in the Wolfsberg ravine. Parquin had a chapel built for Catholic worship. Between 1825 and 1830, a stately ice cellar was also constructed to store the ice needed in summer, and the remise (coach house), which still exists to this day, was also built in the mid-1820s.

In addition, French landscape painter Georges Viard was commissioned to capture the château and its surroundings. In 1828, Godefroy Engelmann's (1788–1839) lithographic institute in Paris published the «Album de Wolfsberg», featuring 12 hand-colored lithographic views. In 1825, the château owner used targeted advertising to promote the modern guest house to members of high society by having a brochure printed in French and English and distributing it across the world.

The press was also used to promote the guest house: a report in the St. Gall newspaper «Erzähler», dated May 6, 1825, likened this tiny spot above Ermatingen to paradise on earth. The guest books from that period have been lost, but French historian Alexandre Buchon (1791–1846) wrote, «Hardly a day goes by that you don't spot some French or foreign celebrities. Chateaubriand, Alexandre Dumas, Casimir Delavigne, Madame Récamier, Sophie Gay, her daughter Delphine Girardin, and Madame Doumère have all visited Wolfsberg at some point.»

The end of the guest house and Parquin's death

Parquin's lifestyle, which was entirely geared towards sensual enjoyment, led to his swift downfall. By marrying Louise Cochelet, he came into the possession of Sandegg Castle near Salenstein, Thurgau. On December 11, 1822, he also bought the dilapidated Salenstein Castle. Owning three properties was a heavy burden for Parquin, who was not very wealthy in any case.

What's more, following the death of his wife in 1835, Parquin was persuaded by the son of Hortense, Prince Charles Louis Napoléon (1808–1873), who grew up at Château Arenenberg and became Emperor Napoleon III, to take part in a coup d’état. Parquin hoped that this would improve his financial situation.

If they had been successful, this coup would have led to the resurgence of the Bonapartist regime in France. But it failed, and went down in history as the «Strasbourg coup». Parquin was tried in court and thanks to a defense speech delivered by his brother, a lawyer based in Paris, he was finally acquitted.

He was not as fortunate the second time round: following his participation in another attempted coup in Boulogne, he was sentenced to 20 years' imprisonment. Until his death in 1849, he spent his days in the citadel near Amiens, writing his war memoirs and seeking comfort from the view of the road to Paris from the small window of his cell.

Meanwhile, at Château Wolsberg, financial ruin could not be avoided and the estate went bankrupt in 1839.

Joseph Martin Parry

Joseph Martin Parry

The next owner, English country gentleman Joseph Martin Parry, was met with a largely neglected estate in Wolfsberg. Within a short period of time, he had a model farm built. Among other things, Parry introduced the four and six-year rotation of fodder and improved the oat and wheat yield by sourcing selected seeds from England and Germany.

In 1847, the château complex passed to Rudolf Kieser from Lenzburg. This marked the beginning of a difficult time for Wolfsberg: due to property speculation, the châteauand the Parquin House were sold separately, and between 1851 and 1865, the buildings changed hands in rapid succession.

The Bürgi family

The Bürgi family

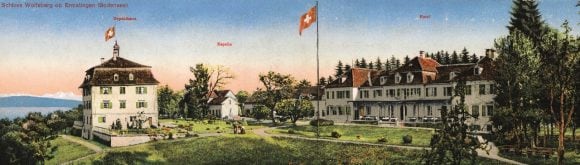

It was not until the arrival of Karl Bürgi-Ammann that the two properties were reunited. Bürgi came from a hotelier family from Arth, Schwyz, who had opened Rigi-Kulm's first guest house in 1816. In keeping with family tradition, the new owner intended to transform the Parquin House, which he had acquired in 1865, into a spa hotel. He had a sun terrace built along the north side and a bathing house with cabins constructed on the west side. The old château, which he bought in 1889, was used as an annex, while the neighboring vineyard, known as «Bernese House», was demolished.

After Bürgi's death in 1891, his son, who had the same name as his father, took over the business and had the forest paths restored and benches installed. As an avid collector of antiques, over the years he gathered a considerable collection of furniture, weapons, pewter, and prehistoric objects, which he exhibited in the Taproom in the new château. Some of these pieces are now on display at the Swiss National Museum in Zurich.

The outbreak of the First World War brought the flourishing business to a premature end. In August 1914, the predominantly German guests left swiftly. In 1917, a convalescent home for the children of German prisoners of war was set up in the east and central wings of the Parquin House. Towards the end of the war, Karl Bürgi-Trescher provided accommodation for the families of some interned German officers. These were the spa hotel's final ever guests.

In 1918, Château Wolsberg passed to Erwin Richard Lauber. He had comprehensive renovation work carried out, including having the bathing house and the «Eremitage» demolished and the slope to the north of the Parquin House leveled out. On the east side of the old château, a walkway covered with hollow bricks was built and the gardens were given a makeover by Rorschach landscape architect Fritz Klauser (1885–1950).

In 1925, the estate was sold to factory owner Edmund Oederlin-Moersdorff, who later sold it to Paul Eduard Meyer, a lawyer from Zurich, in 1938. Meyer was devoted to restoring the historical features of the château, the chapel, and the domestic buildings. During this time, he also worked as a crime writer under the pseudonym Wolf Schwertebach. Under his ownership, Wolfsberg became historically significant for its role in military operations.

During the Second World War, Captain Meyer was entrusted with several sensitive assignments by the head of the Swiss military intelligence service, Colonel-Brigadier Roger Masson (1894–1967). As a result, between 1939 and 1945, Wolfsberg became a hub for contact between neutral Switzerland and representatives of the Third Reich, and its owner became known as «Spezialmeyer». Secret meetings were held between Masson and Brigadier-General Walter Schellenberg (1910–1952), the head of the German foreign intelligence service.

The head of the Swiss Army, General Henri Guisan, was also kept closely informed about these meetings since he wanted to get in touch with Schellenberg himself in order to dispel any doubts about Swiss neutrality.

These texts are largely based on the Swiss Heritage Guide by the Society for the History of Swiss Art SHSA (www.gsk.ch), published in collaboration with Wolfsberg: Cornelia Stäheli, Château Wolfsberg near Ermatingen, 3rd, revised edition, Bern 2013.

Where tradition meets modernity

Where tradition meets modernity

The frequent change in ownership since the 16th century has inevitably led to drastic architectural alterations. Hardly anything remains of the original building constructed in the 1570s. Despite this, the château and grounds have stayed as a unit as they have evolved through the centuries, retaining the charm of a stately residence in largely undeveloped surroundings. The present owner, UBS, aims to preserve and maintain this part of Swiss cultural heritage.

Description

Description

The stately complex is divided into two groups of buildings – one old one and one new one. The historical buildings situated closer to the lake – comprising the château, the Parquin House, the chapel, the library, and the remise (coach house) – together with the covered walkway form an ensemble closed on three sides, surrounding a grass and tree-lined courtyard.

The new buildings, which are set back towards the edge of the forest in the south-east, are clearly separated from the old buildings, with a long colonnade at the main entrance forming a link between the two.

The three-story château is the oldest building on the site. Its current baroque style is a result of its renovation during the 18th century. Today, the château contains reception rooms and five exclusive suites. Adjoining the east facade of the château is the French garden.

Exterior

The château's south facade faces the remise. The compact building features a mansard roof with dormer windows. The onion-topped belfry on the roof houses a bell from the former St. Michael's charnel house in Arth (Schwyz). The original one, which is now known as the «Zollikofer» bell, is located in the foyer.

Simplicity and a sparing use of decorative elements characterize the lightly plastered facades, which are framed by pilaster strips at the corners. The (incorrect) date of 1590 has been added above both the arched cellar portal on the north side and the main entrance on the south side.

Adjoining the east facade is a walkway that borders the symmetrical French garden on two sides. The center of the garden is embellished by the railings of a former well.

Interior

The interior of the château was thoroughly renovated between 1972 and 1975. 1994 saw further renovation and conversion work, during which the original room divisions were retained but the mansard floor was converted into living space. In the most recent redesign, undertaken between 2011 and 2012, the two upper floors and the mansard floor were remodeled in line with the baroque style of 1732, with the addition of some modern elements, creating five luxury suites.

The ground floor is divided into two long, rectangular reception rooms. The foyer has a beamed ceiling with modestly contoured panel boards, and most likely dates back to the original building that Junker Wolf Walter von Gryffenberg had built in 1576.

The castle hall facing the lake was formerly divided into two parts. A newer, narrow staircase leads from the foyer to the first floor. The rooms on this floor, a club room, a parlor, and the «Parry» guest room, can be accessed via a narrow central corridor and face partly towards the lake and partly towards the courtyard.

The second floor and the mansard floor have an almost identical room layout and now house the four guest rooms: «Guisan» and «Zollikofer» (on the second floor), and «Gryffenberg» and «Högger» (on the mansard floor). Half of the lake-facing guest room on the second floor is spanned by a Régence stucco ceiling, which was probably constructed in 1732 under the supervision of Johannes Zollikofer.

Furnishings

Among the few preserved historic pieces of furniture are the four white glazed, tiled stoves. The numerous present-day furnishings purchased by UBS in the 1970s include a late Gothic double-story cupboard of South-German origin with a richly pierced front that is gilded and painted, as well as four carved niche figurines.

Located to the south-west of the château, the Parquin House was used to accommodate guests and originally had a riding hall in the central part. This elegant and classicist building was constructed in 1797 by the wealthy merchant Baron Jean Jacques Högger. Bonapartist Colonel Charles Parquin subsequently renovated it to include the furnishings that characterize the interior to this day. He redesigned the building in 1825 to create Thurgau's first guesthouse.

Exterior

The Parquin House's elongated structure is penetrated by a two-story corner and central pavilion with hipped mansard roofs. Decorative elements are integrated into the corner edges of the light-yellow plastered facades.

On the house's north facade, which faces the lake, is an impressive columned portico with a balcony above it. Directly in front of the main entrance on the south side is a 17-meter-deep well, which dates back to the 1870s.

Interior

The interior of the building was completely hollowed out and modernized between 1972 and 1975. On the ground floor, beyond the spacious entrance hall are three generously designed Empire rooms, which were constructed under Charles Parquin. They were restored to their original condition, and today are used as dining rooms for up to 150 people.

The Yellow hall features honey-colored wallpaper. On the east wall hangs a near life-size portrait of Napoleon III in a gilded oval frame, while opposite is the more modest portrait of his famous Uncle Napoleon I (both on loan from Château Arenenberg). A white-tiled cylindrical stove with brass ornamentation showcases the room's historical elegance.

The Red hall is decorated in shades of subdued beige and English red. The north wall features a mirror with a blue architectural frame and figurative gold appliqués. On the east wall is a graceful Empire fireplace with a chimney breast featuring ornamental decorations. Both pieces are original furnishings.

The Tent hall, which has the same shape and color as a Napoleonic commander's tent and is now a listed building, was inspired by the tent room at Château Arenenberg. The ceiling structure and walls are decorated with vertical blue-and-white striped wall coverings, with a painted, golden lambrequin (replica of a curtain) under the sloping sections of the ceiling.

The remise, which was constructed in 1825 under Charles Parquin, was originally used as stables. Today, the only reminders of its erstwhile function are the two characteristic three-centered doorways and the elevated, gabled door on the south side of the house. The single-story, elongated gabled construction is joined to the Parquin House via a gate-like connecting tract.

From stables to a bar

Since its complete renovation by UBS, hardly anything reminds of the remise's previous function as stables. In 1997, the remise was renovated and rebuilt. The same year, a garden area was created. This park, known as the English Garden, is modeled after a garden in the western part of the Kensington Gardens in London.

Today, the remise houses leisure and meeting rooms, some of which were redesigned between 2001 and 2002. On the ground floor, next to the central rooms, is a lounge with a bar. Upstairs, there are two clubrooms for cozy get-togethers, the Granary and the Barrack room.

Between the château and the remise lies the chapel, which was built by Charles Parquin around 1830. It consists of a tower with a square floor plan, which houses the chapel room on the ground floor, and a chancel closed on five sides. The south facade features a brightly painted sundial. The library adjoins the chapel on the west side. None of its original furnishings survive today.

The small prayer house

Five neo-Gothic windows, some of which are fitted with bullseye panes, and a round window, divide the facades. The tower is covered by a pyramid roof with a belfry. Two gravestones made of sandstone flank the north portal. They were moved here from Ermatingen Church after it was renovated in 1899. Their (supplemented) inscription refers to former owners of Wolfsberg. On the left: the Gelderich von Sigmarshofen family; on the right: Johannes Zollikofer von Altenklingen.

Inside, the division between the nave and the chancel is marked by a circular arch. Both parts of the room have simple plastered ceilings. The floor is covered with clay tiles.

Furnishings

Nothing is left of the original furnishings, some of which Parquin had brought from Sandegg Castle in the nearby village of Salenstein (Thurgau) around 1830. Today, an altar table with a profiled and partially gilded front stands in the chancel. It is said to have come from Klingenzell Chapel near Mammern. The walnut pews and the oaken rood screen fragment (which acts as a barrier to the chapel room) were moved here from their former location in Ermatingen Church.

The two north wall niches house a Venetian ciborium (chalice) from the first half of the 15th century on the right and a Lower Rhine burial and mourning group made of wood dated around 1510 on the left. The carved figure on the south wall console, created in the 14th century by a South-German master, most likely depicts St. Dorothea, the apple being the identifying attribute.

UBS added all the smaller pieces of furniture and equipment to the chapel. They stem from various sources.

Half of the gabled roof construction attached to the chapel was originally part of the chapel, while the western part of the building was formerly used as a washhouse and even as a chemical laboratory in the 1890s. In 1975, the library was set up by UBS.

Much more than a place for books

The building's exterior has an understated look. On the west flank is a fountain adorned with a large shell, the symbol of St. James and pilgrims.

The interior of the building was completely redesigned between 1972 and 1975 by architects Rudolf and Esther Guyer. The narrow room, which is mainly clad in wood with an open view of the roof beams, was furbished with a gallery on three sides. It can be reached using the neo-Gothic spiral staircase. Until 1975, this stairway was used to access the upper floor of the château. The iron tower clock on the west wall also comes from the château and was constructed in 1540 by Laurentius Liechti (†1545), the founder of the Winterthur Liechti clockmaking dynasty. The clock dial is located on the outer wall.

Until the start of the internet era, the library served as an information center with the latest publications from the fields of leadership, management, banking, business, art, culture, and politics. Today, it houses publications and exhibition catalogs from the fields of art and architecture.

The ice cellar was built in a quiet spot to the south of the new building complex under the supervision of Charles Parquin between 1825 and 1830. It was restored and fitted with a space-saving spiral staircase between 2006 and 2007.

Inconspicuous exterior

Featuring a north-facing covered entrance porch, the cellar looks fairly unassuming from the outside, but it contains a chamber of impressive proportions (max. height: 8 m; max. width: 5.1 m). The hollow egg-shaped structure extends several meters underground and its floor and walls are characterized by the natural rock surface in the lower section and exposed brick cladding in the upper section. The floor features a circular drain for any excess water. In the vaulted ceiling, you can still see the original hoisting equipment that was used to raise and lower the blocks of ice.

The new conference building was designed by Zurich-based architects Arndt Geiger Herrmann and was completed in the spring of 2020 following over two years of construction. It replaced the previous building built by Rudolf and Esther Guyer between 1972 and 1975. Architecturally, it forms a unit with the three-part hotel wing, also built by Arndt Geiger Herrmann, which was completed in 2008 after three years of construction.

Thanks to their deliberately low height, the new buildings blend in well with their rural surroundings. Both the conference center and the hotel building offer transparency, clear lines and consideration for the landscape and the unique location of Château Wolfsberg.

These texts are largely based on the Swiss Heritage Guide by the Society for the History of Swiss Art SHSA (www.gsk.ch), published in collaboration with Wolfsberg: Cornelia Stäheli, Château Wolfsberg near Ermatingen, 3rd, revised edition, Bern 2013.

Acquisition by UBS

Acquisition by UBS

In 1970, the Schweizerische Bankgesellschaft (known today as UBS) acquired the château complex and the surrounding 12 hectares of land in order to convert it into a training center. Extensive renovation of the existing historic buildings and construction of the new buildings were carried out by Zurich-based architects Esther and Rudolf Guyer and completed in spring 1975. The training center opened on May 8 of the same year.

Ongoing development

Ongoing development

Between 2005 and 2008, the three-part hotel wing with 122 guest rooms was redesigned by Zurich architects Arndt Geiger Herrmann. At the same time, the historic ice cellar was restored and a new underground garage with 90 parking spaces was built. Under the direction of the St. Gallen architectural firm Klaiber Partnership AG (today Forma Architekten AG), the castle was renovated from 2011 to 2012 and, with the addition of modern elements, brought closer to the baroque building fabric of 1732. The most recent structural changes took place from December 2017 to March 2020 with the construction of the new seminar and conference building, again by Zurich architects Arndt Geiger Herrmann.